I recently revisited Powys – land of my fathers – continuing my ‘pilgrimage’ to sites important to Welsh history. Cilmeri and Abbey Cwm Hir – associated with Llewelyn ap Gruffudd – resulted in a file of photographs … and a poem, in the form of a bardic lament, albeit in English, in honour of Y Llyw Olaf.

Author: Sharon Larkin

October – Poetry Month

For poets, every month is a poetry month, but in the UK we have National Poetry Day and a series of festivals around Britain which make every October a feast of poetry.

This year’s Cheltenham Literature Festival includes: Gillian Clarke and Alison Brackenbury, Luke Kennard and Melissa Lee-Houghton, Matthew Hollis and Blake Morrison, Simon Armitage, Sarah How and Rebecca Perry … and local writers and poets in a Gloucestershire Writers’ Network event. I’m delighted to have tickets for all of these (not to mention a ticket for Ian McEwan, taking about his new novel, Nutshell. He read the opening few pages at his event last night and it struck me as not only witty, humorous, astute … but, yes, poetic). Cheltenham Literature Festival

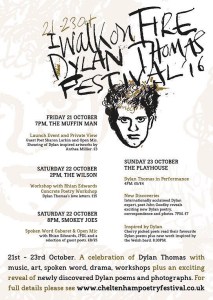

Nearby we have Swindon Poetry Festival 2016 and Bristol Poetry Festival 2016 going on, and later in the month, a weekend festival here in Cheltenham celebrating Dylan Thomas, run by Anna Saunders/Cheltenham Poetry Festival I Walk on Fire and featuring Rhian Edwards and John Goodby, artist Anthea Millier, and local poets and writers:

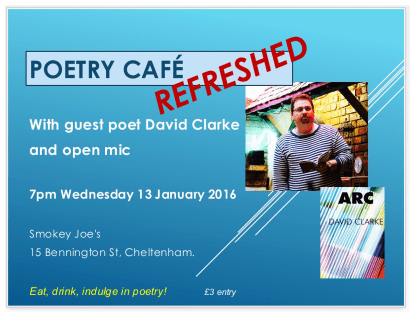

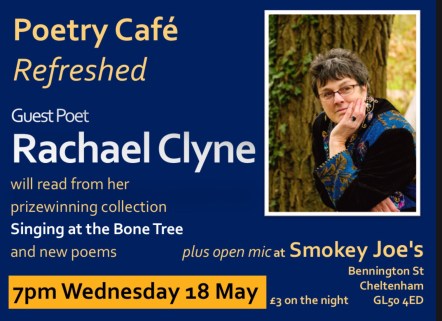

Meanwhile, regular events continue in the town: Angela France’s Buzzwords featuring David Clarke and Cliff Yates on 2 October, Cheltenham Poetry Society’s ‘Views on Ted Hughes’ night on 4 October, Poetry Café – Refreshed at Smokey Joe’s on Wednesday 19 October, Cheltenham Poetry Society’s regular poetry reading group and writing group meetings on 18 and 25 October. In other Gloucestershire towns, monthly writing/poetry groups run by Rona Laycock in Cirencester and Miki Byrne in Tewkesbury will be meeting at New Brewery Arts and The Roses Theatre respectively.

Yes, October is a month of feasting on poetry!

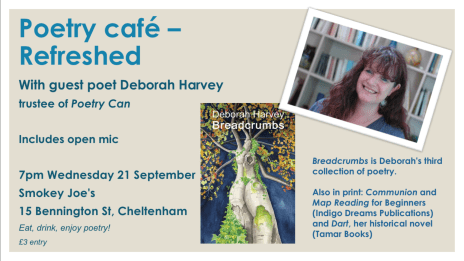

Poetry Café – Refreshed, September

September’s Poetry Café – Refreshed in Cheltenham welcomed guest poet Deborah Harvey who gave us an unforgettable evening of powerful poetry. A strong open mic was represented by David Clarke, Michael Newman, Peter Wyton, Jennie Farley, David Ashbee, Belinda Rimmer, Sam Loveless, Gill Wyatt, Stephen Daniels, Chris Hemingway, Flash and hosts Roger Turner and Sharon Larkin. We were delighted to welcome poets from Bristol and Swindon to Poetry Café – Refreshed, and look forward to guest poets from Worcestershire during October and November.

Thanks to Mr L for taking the photos in this video record of the evening.

Happy birthday, Refreshed!

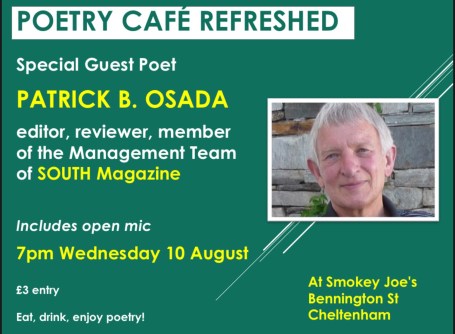

On 10 August 2016, Poetry Café – Refreshed celebrated its first birthday. We were delighted to welcome Patrick Osada, who is on the management board of South magazine, as the guest poet on this special occasion.

Poetry Café – Refreshed, a monthly event, hosted by Roger Turner and organized by Sharon Larkin (yours truly), is held in the unique surroundings of Smokey Joes in Bennington St, Cheltenham – a café with an informal and relaxed atmosphere, an American diner-inspired décor given a British twist … and offering an irresistible menu.

Smokey Joes – a relaxed, informal atmosphere

Smokey Joes – a relaxed, informal atmosphere

We’ve been enjoying some superb poetry. Over the past year, we’ve had a succession of exciting guest poets come to read and perform for us:

- John Alwyine-Mosely – August 2015

- Tom Sastry – September 2015

- Nina Lewis – October 2015

- Avril Staple – November 2015

- Brenda Reid-Brown – December 2015

- David Clarke – January 2016

- Sue Johnson, Bob Woodroofe and Joy Thomas – February 2016

- Paul Harris – March 2016

- Matt Duggan – April 2016

- Rachael Clyne – May 2016

- Lesley Ingram – June 2016

- Ben Banyard – July 2016

- Patrick Osada – August 2016

… and the quality of the poetry from the open mic poets has been high too!

At the ‘anniversary edition’ of Poetry Cafe – Refreshed on 10 August 2016, at the open mic we had: David Ashbee, David Clarke, Miki Byrne, Annie Ellis, Jennie Farley, Robin Gilbert, Sharon Larkin, Michael Newman, Stuart Nunn, Belinda Rimmer, Roger Turner, Gill Wyatt.

We’ve had many more poets join us at the open mic over the past year, including Kathy Gee, Sarah Bryson, Polly Stretton, Judi Marsh, Holly McGill, Anna Saunders, Howard Timms, Marilyn Timms, Kev Alway, Courtney Hulbert, Briony Smith, Chris Hemingway, Aled Thomas, Gill Garrett, Elizabeth Chanter, Michael Skaife d’Ingerthorpe, Samantha Pearse … and on one memorable occasion Dom Joly.

We look forward to the next year of Refreshed. Guest poets for the next three months are:

- 21 September 2016 – Deborah Harvey

- 19 October 2016 – Kathy Gee

- 16 November – Claire Walker

Please make a note of 16 November and 14 December, the last two Poetry Café – Refreshed events for 2016 … and we already have a number of exciting guest poets lined up for 2017!

We’re most grateful to Vickie Godding and the staff at Smokey Joes for being so welcoming and accommodating towards us. We love your waffles!

And thanks to TL for taking photos at Poetry Café – Refreshed.

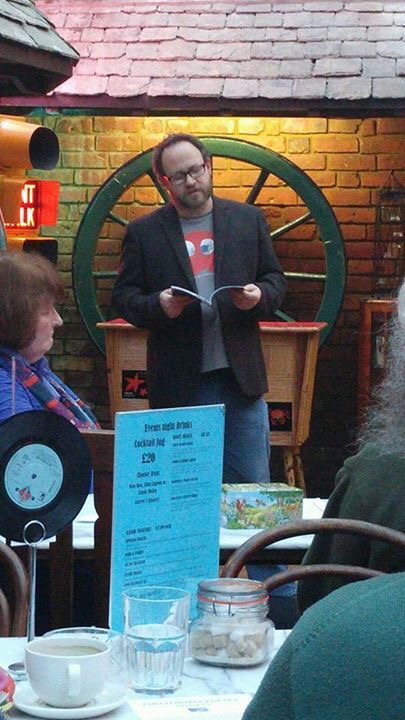

Some photographs from our first year:

Cheltenham – Part 2 (and other news)

Super write-up of Ben Banyard’s visit – as guest poet – to Poetry Café – Refreshed, Cheltenham in July,

As regular readers of this blog will know, and possibly roll their eyes to hear again, being part of Jo Bell’s 52 has brought me an embarrassment of riches. Take my recent reading at Poetry Café Refreshed in Cheltenham, for instance – one of its organisers, Sharon Larkin, was a fellow 52er and I was delighted to accept her invitation to be their guest reader.

The venue is the splendidly quirky Smokey Joe’s in Bennington Street, which is decorated in the style of a 1950s diner, complete with period fixtures and fittings. The performance space is a lovely bright and airy room at the back, which includes a jukebox fashioned from the back end of a vintage Mini and even a selection of old coin-operated arcade games.

The format of the event is very civilised – there’s an open mic section where everyone gets to read a couple of their…

View original post 445 more words

Trefin Mill – William Williams Crwys

I was recently prompted by musician and fellow-poet, Chris Hemingway, to find the text of a poem in Cymraeg by William Williams (1875 – 1968), bardic name Crwys, and to translate it into English. William Williams Crwys

Chris had become aware of the existence of the poem – Melin Trefin – on his visit to Trefin – roughly half way between St Davids and Fishguard on the north Pembrokeshire Coast. He asked Facebook friends if anyone knew of a translation. That was all the prompting I needed. Trefin Mill

To my shame, I didn’t know the poem itself although I was acquainted with the name William Williams Crwys – an Archdruid (chief bard of the Gorsedd of Bards) and three-times winner of The Crown at the National Eisteddfod. One of the greats. Here is a picture of HM The Queen (then Princess Elizabeth) and Crwys at the National Eisteddfod at Aberpennar (Mountain Ash) on 6 August 1947 Princess Elizabeth and Archdruid William Williams Crwys.

In fact, the poem is well loved by Cymry Cymraeg … and came 21st in a BBC Wales online poll of Welsh-speakers’ favourite poems in 2003. I soon tracked the text down:

Melin Trefin

Nid yw’r Felin heno’n malu

Yn Nhrefin ym min y môr,

Trodd y merlyn olaf adref

Dan ei bwn o drothwy’r ddôr,

Ac mae’r rhod fu gynt yn chwyrnu

Ac yn rhygnu drwy y fro,

Er pan farw’r hen felinydd

Wedi rhoi ei holaf dro.

Rhed y ffrwd garedig eto

Gyda thalcen noeth y ty,

Ond ddaw ned i’r fal ai farlys,

A’r hen olwyn fawr ni thry,

Lle doi gwenith gwyn Llanrhiain

Derfyn haf yn llwythi cras,

Ni cheir mwy on tres o wymon

Gydag ambell frwynen las.

Segur faen sy’n gwylio’r fangre

Yn y curlaw mawr a’r gwynt,

Di-lythyren garreg goffa

O’r amseroedd difyr gynt,

Ond’ does yma neb yn malu,

Namyn amser swrth a’r hin

Wrthi’n chwalu ac yn malu,

Malu’r felin yn Nhrefin.

Here is my translation – aiming more to be faithful to the Cymraeg than to be a poetic rendering:

Trefin Mill

The mill is not grinding tonight

in Trefin at the edge of the sea.

The last pony, from beneath its burden,

turned from the threshold towards home

and the wheel that used to rumble

and grumble through the area

has, since the old miller died,

made its last turn.

The kindly stream still runs on

past the bare forehead of the house

but it no longer comes to mill the barley

and the big old wheel won’t turn again.

Where the wheat of Llanrhiain

lay at summer’s end

now there’s only a trace of seaweed

and a few green reeds.

The stone at rest that watches the place

in the thrashing rain and the wind

is a letterless memorial

to the jollity of former times.

Nobody is milling here now.

It is a time of dereliction

– the grinding down

of the mill at Trefin.

Notes:

It’s virtually impossible to render the musicality of the Welsh, with all the alliteration and rhyme … the cynghanedd or chiming harmonies for which poetry in Cymraeg is justly famous.

The phrase “mynd am dro” – literally to go for a turn, is the common idiomatic way of saying “to go for a walk”. So the Welsh for a wheel turning for the last time carries in it the idea of the miller making his last turn too ie going for his last walk, or even giving his last performance (as we call an act on stage a “turn”).

Thus the mill and the miller are one unit, and hence their fate is linked, and hence the mill personifies the miller. So, when the miller does his final “turn” so does the millwheel – and so does the pony that turns the grindstone. Pony and man slough off their “burden” and “go home”.

The millstream that powered the wheel is also personified. It is “kindly” – suggesting the miller was too. (I hesitated to use the word “grumbled” in association with the sound of the turning millwheel, because it was clearly out of character with the miller, but the Welsh has two chiming, onomatopoeic words and I needed something similar to accompany “rumbled”).

While the “kindly stream” no longer visits the mill (the millrace presumably dries up), the (main) stream still passes the “bare forehead” of the (mill)house … again allying building to miller and vice versa.

In the final stanza, there is a feeling that the mill begins to tumble down, on the death of the miller – to fall into ruin even as the miller’s remains are consigned to the earth. Grain is no longer being ground down; body and building are being broken down now.

The millstone bears no inscription but acts as a gravestone for mill and miller, exposed to the elements – the wind and the thrashing rain). As a translator, I was pleased to come up with a word to describe the rain beating down that sounds so much like “threshing”.

Alas, the closest I can come to emulating the cynghanedd is in the proximity of “letterless” and “jollity” with their repeated t and l sounds. Saying those two words with a lilting Welsh accent that gives a long stress to the first syllable, provides some impression of the satisfying effect a poet can achieve with the cynghanedd.

I found the exercise very enjoyable. Thanks Chris!

Lines that cannot disappoint

I’ve been intending to start reviewing collections and pamphlets here for some time. Here’s the first one …

The title of this review is a quotation from the poem Nightly, two thirds of the way through Zelda Chappel’s haunting and beautiful collection, The Girl in the Dog-tooth Coat, published by Bare Fiction Poetry (2015). Having read and reread the sixty poems in the collection, I can state categorically that I have failed to find a single line that disappoints.

The title of this review is a quotation from the poem Nightly, two thirds of the way through Zelda Chappel’s haunting and beautiful collection, The Girl in the Dog-tooth Coat, published by Bare Fiction Poetry (2015). Having read and reread the sixty poems in the collection, I can state categorically that I have failed to find a single line that disappoints.

This can be what you want it to be – the inviting title of the first poem – is a welcoming and generous offer to the reader who will do well to reciprocate, by spending time with the poems so that their shifting tides can uncover fresh ground on each visit. An intuitive reader will follow signs – a sodium trail or a glisten of cuckoo spit – in the quest for insights into what the poet might want the collection to be.

The language of the collection is clear and cool yet the poet skillfully controls the rate at which a reader’s understanding builds. In the poem On not holding on to a bird, towards the end of the collection, we are given another offer: Let me talk to you in coded tones until you begin to know what there is to decipher. Elsewhere, the poet refers to Glass making a show of transparency while I learn ways to be opaque. Thus we are encouraged to keep peering through misted lenses, landscapes and mindscapes while clarity gradually emerges, mindful, though, that it is a poet’s prerogative not to make things crystal-clear if they choose not to. This generously leaves an invitation for the reader to bring her/his own experience to the work.

Glass, then, in its many guises, is one of the important metaphors in the collection. So too is salt – the sodium trail. It comes from sea water, is borne on the wind, stings cheeks and eyes, lodges in hair. It pervades relationships. It is a tartness on the lips, at times a bitterness. Stars, whether observed directly or reflected in water, convey both a sense of remoteness and an illusion of ‘graspability’ – much as liberty, that desire of youth – may have to cede to the fear of freedom, as a greater reality. While there is a sense of freedom in the wild marshland, it comes with the risk of getting lost in the mist, of drowning. So too in the quests for identity and for another to share one’s life with – the uncertain, potentially perilous boundaries between self and other. Such dichotomies are mirrored by occasional glimpses into a domestic interior or a more urban environment, but the ever-present backdrop is the ever-changing coastal landscape where the blurred edges of land, sky and sea merge into Turneresque abstraction.

The weather, the changing seasons, varieties of birds, parts of the body – all play key roles in the imagery of this collection, as do elements associated with the crafting of textiles: fabric, thread, the acts of sewing and unpicking. These motifs carry the themes which gradually emerge – as the craft wills: the search for self and other, freedom and commitment, reticence and open communication. There are attempts to focus in uncertainty, to define boundaries, to make the fuzzy clear – and conversely there is an imperative to retain opacity as a form of self-protection, privacy, and perhaps to preserve a degree of mystery. These contrasting impulses blend and merge in the intertidal zones, the shifting sand, the deceptive saltmarsh, the unfocused filtering of earth, sea and sky. Romney Marsh and Dungeness are a fitting backdrop for the uncertain interplay of relationships and psychologies in the collection.

Precision of focus comes as the lens is adjusted; marshland firms up into the more solid territory of measurement, mechanical things, numbers even. However, we are not encouraged to grasp after these for easy ‘answers’. For me, the loosening and tightening focus are no more clearly contrasted than in the poems Winter and Dead cert, on facing pages, towards the end of the collection. Winter encapsulates many of the elements encountered in the poems – the coalescing of landscape, climate, season and the human’s place in them; familiar elements of sea, tide, salt, sand, grit, light, dark, sun, moon, horizon, shadow, fog, cold – the merging and the blurring of these – contrasting with the hard-edged pavement, strident bird calls, the sting of commuter hours. On the opposite page, is a poem of precision and certainty – but it is a dead certainty – the dysfunction of a broken clock, cracking skin. The ‘you’ of this poem is calculating, acquisitive, destructive: But there’s an air of certainty about it; the way you split hairs and bone, make small piles of me to store and count up later. The ‘I’ of the poem consequently becomes almost Plathian in her pain: Even with my eyes closed I can watch the way you peel back my skin like an offering line your pockets with my ash. The juxtaposition of Winter and Dead Cert thus presents us with insights into an asymmetric pairing in terms of emotional quotient. The form of the poems is similarly contrasting – five spare couplets for Winter, two seven-line blocks, defying the label of sonnet or prose poem, for Dead cert – a poem which therefore ironically persists in its ‘uncertainty’.

In terms of shape, colour and texture, the poet is a consummate artist. An initial reading might give a largely monochrome impression, with diffusing shades of light and dark gradually solidifying until we achieve clarity – significantly, in the black and white pattern of the girl’s dog-tooth check coat. But there are intense splashes of colour throughout the collection, startling us out of the dreamlike atmosphere of the often-misted landscape. In Red Sky we are given a shepherds’ warning in crimson and rose of how dangerous the marsh is. A sense of fear is instilled early in a child’s muffled ears by an anxious mother – as memorable and as potentially damaging as earache. A child hears and heeds the warnings but must strive to go beyond them if they are to resist a restricted existence: the vastness of longing for water to take what the wind gave us, all those fears we hold of drowning. We want to hear their warnings. We’ve no choice but to slip our skins. Daring – the desire for freedom and escape – challenge caution and restraint. The image of ‘slipping’ in relation to ‘skin’ returns repeatedly as an important motif in several poems centering on relationships, as we shall see later.

In Lucky, colour floods in. Blue of sky and sea merges with greens of land, washed on a broad canvas, until our eyes are sharply pulled to the foreground in a flash of primrose. With the perception of a child, both poet and reader sense details close to the ground, through eyes, feet and backs of legs. Here we are near enough to the pavement to see the glisten of cuckoo spit, reminding us of the trail of sodium on the paving in first poem. Such are the signs left for a reader to read. In Lucky the sun breaks through again, but it is sunset on a large canvas and clarity and definition fade: I loved the sunset because the blurring didn’t matter.

Thwarted communication and difficulty in expressing emotion are similarly subtly expressed through metaphor. Our tongues get folded, stealing away my speech delicately merges reticence with the act of kissing. Equally exquisite is the description of whispering: open mouths writing letters, lipped words placed softly in ears precisely. In the transitional poem Pause, the theme of stalled communication is beautifully carried by a singing metaphor: You’ve no idea how I could sing a thousand words and still not be able to speak them. I tell you there’s something you don’t understand between the punctuation. After the birth of a child, there seems to be an easing of communication – for a while. But in the poem Lucky, which combines many of the themes of the collection, communication sticks, and a sense of separateness and alienation appears to return: You could have talked the world into stopping. It did for a while. I felt it …”

The importance of edges and margins, as painted in the backdrop to the collection, is mirrored in the desire for boundaries to be maintained, or crossed, between one person and another. This is clearly related to how far an individual’s identity extends – the border where one person ends and another begins. Personal space is repeatedly tested in the collection, with images of ‘slipping’ and ‘sliding’ between clothing and flesh. The poet writes of a fetish for transcendence being ‘easier’ – easier, perhaps, than defining the extent of an individual’s identity: These days it’s slipping through flesh which we know can be done in silence. In Flesh the poet writes of shrinking as you fill the space I leave between my skin and bone. In Trickster: No one but me sees the way your hand slips under. In the transitional poem Pause there is an exquisitely intimate development in the theme: Now your hand between my under-skins gets left there. It helps you know which bits you’ve touched, which ones are still to go.

There are so many ‘favourite poems’ in this collection, and so rich is the imagery built up layer on layer, that I could write at length on each poem in relation to the rest. But I need to draw this review to a close. I therefore choose three: the achingly beautiful Deciphering the sea for my baby, Dear boy and Post-natal as my current favourites but these could change at my next reading. There are so many excellent poems in the collection that it isn’t possible to limit favourites to two or three.

The final poem, Numbers, brings precision and apparent clarity – the ‘mechanical’ threads – together, yet resolution remains elusive. The last three lines almost mischievously remind the reader to resist reaching for obvious conclusions, even after repeated rereadings. The glass retains opacity, the landscape remains blurred, boundaries are still uncertain:

I gave them all my numbers / knowing they mean nothing. They mistook them / for answers. I knew they would

… splendid lines with which to conclude a collection of poems that cannot disappoint.

Zelda Chappel’s collection The Girl in the Dog-tooth Coat is available from Bare Fiction Poetry

Out – explaining a poem

The latest edition of the Maligned Species ebooks from Fair Acre Press has been published recently, concluding a quartet of poetry publications during February celebrating Spiders, Grey Squirrels, Frogs and Stinging Nettles. The series is expertly published by Nadia Kingsley.

I’m pleased that my poem “Out” was accepted for the latter edition. It deals with exclusion and ostracization because of perceived “difference”, telling of a young man who takes a lunchtime break from office bullies to search for the solace available in the natural world, where authenticity is to be found and celebrated. He literally grasps the nettle of facing up to the pain of life and the choices that have to be made. The resulting discomfort is preferable, stimulating even, compared with the suppressed rage of silently tolerating prejudice, harassment and social cruelty … as many who resort to self-harm in response to abuse will testify. The stinging nettle provides an appropriate metaphor.

Why explain the poem? Isn’t it better to allow audience to interpret? Yes. Almost always, yes. And often a reader or listener will pick up on some significance that the poet themselves hadn’t fully realized. But, having been told recently that the imagery in another of my poems was impenetrable, I thought this was an opportunity to talk about the kinds of psychologies that might be lurking beneath the surface of poems. Sometimes I ask my reader or listener to work a little harder to grasp my nettles. I don’t think that’s a bad thing for the recipient. Coming to the aha! moment after putting in a little extra time and effort has to be more rewarding than the quick flick of an obvious reveal. Well, doesn’t it?

Anyway. Here’s the link to the Fair Acre press shop where you can download the entire Stinging Nettles ebook or pdf for £2.99, proceeds going to the charity Plantlife.

Fairacre Press bookshop

The tremendous cover at the top of this blog post is by Peter Tinkler and is especially sympathetic to “Out” and other poems in the collection by:

David Calcutt, Andrew Fusek Peters, Nadia Kingsley, Liz Lefroy, Emma Purshouse, and John Siddique. Also poems from: Deb Alma, Jean Atkin, Carole Bromley, Tina Cole, Linda Goulden, Jan Harris, Steve Harris, Angi Holden, Janet Jenkins, Chris Kinsey, Patricia Leighton, Mandy Mcdonald, Alwyn Marriage, Rosie Mapplebeck, Gillian Mellor, Nicky Phillips, Pauline Prior-Pitt, Antoinette Rock, Helen Seys Llewellyn, Sophie Starkey, Claire Stephenson, Giles Turnbull, and Deborah Wargate.

Maligned Species

Delighted to have two poems in the Spiders e-book of the Maligned Species project from Fair Acre Press. Here’s a picture of the splendid cover:

The e-book will be available on this link shortly: Fairacre Press Bookshop. costing £2.99. Money from each e-book sold will be donated to Buglife… and could even save a species of spider from becoming extinct! Please support the project by purchasing a copy. Great value for some 40 poems in total, including work by John Siddique, David Calcutt, Jonathan Edwards, Nadia Kingsley Angela Topping, Jane Burn Storybook Art, Sarah Leavesley, Nina Lewis, Maggie Mackay, Jean Atkin, me and many others.

Thanks to Nadia Kingsley of Fair Acre Press for the project and for including our poems. Watch out for other books in the Maligned Species Project – Grey Squirrels, Stinging Nettles and Frogs – emerging on Fridays throughout February.

Refreshed by Poetry

Over recent months, I’ve been pleased to work with Roger Turner to support Poetry Café – Refreshed at Smokey Joe’s in Cheltenham. Roger hosts this monthly event, set in the wonderful American Diner-themed café in an exciting area of the town which is currently undergoing redevelopment. This will soon be a bustling social quarter of Cheltenham, including the Brewery Complex of cinema, leisure facilities and restaurants. Poetry Café – Refreshed includes an open mic.

It has been a great pleasure to invite poets I’ve come to know through Jo Bell’s wonderful 52 initiative to be guest poets at Refreshed. So far this has included John Alwyine-Mosely (August) and Tom Sastry (September), both from Bristol, and Nina Lewis (October) from Bromsgrove – all wonderful poets. Their readings were very well received and we look forward to welcoming other 52-ers to be guest poets over the coming year

On 11 November Avril Staple from Gloucester will be the guest poet at Refreshed. Many poets in Cheltenham and Gloucester know Avril well from Angela France’s wonderful Buzzwords (7pm first Sunday of the month, Exmoor Arms, Bath Road, Cheltenham). I know Avril’s work first-hand from the Creative and Critical Writing MA we did at the University of Gloucestershire in 2010 – and also from Poetry Factory, a Cheltenham-based group we both belonged to during 2012-13, along with David Clarke, Anna Saunders and others.

I’m looking forward to reconnecting with Avril at Refreshed, and with a great crowd of open mic poets. But first, I hope to meet up with Avril and the regulars at Buzzwords this Sunday, 1 November, when Jonathan Edwards and Mike Jenkins will be running the workshop and reading as guest poets. As an enthusiast for Welsh poetry, I am personally very much looking forward to this.

The open mic at Buzzwords is always first rate. Local poets are indebted to Angela France for her tireless work in support of poetry; Buzzwords is the longest-running poetry performance opportunity in the area, with an impressive “back list” of guest poets. Angela teaches at the University of Gloucestershire and gained her PhD there this year. So it is great news that Angela was recently appointed Cheltenham’s Poet in Residence.

It will be great to reconnect with poetry enthusiasts during November at the many events Cheltenham has to offer.