A Gradual Return to Normality or Will Things Ever be the Same?

In 2022 social activities, and real-life poetry events, hesitated back into calendars. Meanwhile, streamed readings, podcasts, and workshops, Zoom launches and open mics continued to flourish … welcomed by poets who were, or are, less mobile, or for whom face-to-face meetings continued to be unwise or unappealing. The huge advantages of virtual events are well acknowledged: national and international audiences for poets’ work, greater diversity of input and output at workshops, and exposure to a much wider range of poetics and cultural traditions. It’s all about extended reach. For some, the climbing stats for Covid, flu and streptococcal infections, as 2022 drew to a close, encouraged another ‘retreat from real life’ … and on-line activities are continuing to save the day. Clearly, a hybrid approach to events is here to stay.

Now for my personalised list of thanks and praise for 2022.

Competitions

In March, I was thrilled to hear that I had won first place in the Dreich ‘Black Box’ competition, for which many thanks to Jack Caradoc of Dreich, and congratulations to all the commended and shortlisted poets. My prize arrived speedily and safely: a huge box of Dreich publications, and a book bag and pen, all in a splendid Black Box decked out with a super white bow. The icing on the cake was the ‘Black Box’ anthology of the winning and shortlisted poems, including my poem ‘Flight Recorder’. Black Box Anthology.

My next competition success was not a poetry prize, as such, but thanks to Intrigue and Mosaic in Stroud for the lovely fedora I won in a competition run by the shop. It might not have been a poem that won it for me, but it was carefully chosen, artfully arranged words! I’ll be wearing the hat to poetry gigs when I have the opportunity! Thanks to the lovely person in the shop who helped me to decide which colour to choose, and who took the in-store photo. And thank you to my friend Sheila Macintyre who not only tipped me off about the competition but met me in Stroud in June for a super catch-up over lunch, after I’d picked up the prize.

Poems Published: in Anthologies, Magazines and On-line

My poem ‘Keyboard Warrior’ made it into the ‘At the Edge of all Storms’ anthology from Dreich in July. I loved the striking cover. Thanks again to Jack Caradoc, and to Cara L McKee. The anthology can be ordered here: At the Edge of all Storms

Five of my poems were published on-line in the ‘Lothlorien Poetry Journal’ in April. They can be read here Lothlorien Poetry Journal. A big thank you to editor Strider Marcus Jones, and thank you, especially, for the overwhelmingly positive words from in his confirming email. Such an enthusiastic and appreciative message from an editor is heartening and gladdening! Unusually for me, the poems all had a fantasy/sci-fi flavour: ‘Receiver’, ‘Reverie’, ‘In Transit’, ‘Visitations’ and ‘Managed Invasion’. Another thank you to Strider for including my work in Vol 11 of the Lothlorien Poetry Journal – ‘Windmills of the Mind’ – a beautiful book, with poems by many poets I admire, published in August, and available to purchase here: Lothlorien Poetry Journal Volume 11

Thanks to Robert Garnham for including my poem ‘Lent in a Time of Coronavirus’ on the ‘Spilling Cocoa Over Martin Amis’ website in April … a super platform for poetry that dares to be humorous, even in plague-ridden times! My poem can be read here: Spilling Cocoa

On a related (pandemic) theme, thanks to Ben Banyard in May 2022 for publishing my poem ‘Dawn Chorus, May 2020’ on-line in ‘Black Nore Review’. Read it here: Black Nore Review

Thanks to Stewart Watkins for publishing another five Covid-related poems of mine in his ‘Pandemic Poets’ anthology in August. It’s full of powerful responses to the pandemic, and available to purchase here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B0B7QJPMR8/ref=dbs_a_def_rwt_hsch_vapi_taft_p1_i3

In October, I was pleased to find that I had a couple of clerihews in the second volume from Smokestack Books ‘More Bloody Clerihews’ – thanks to Andy Jackson and George Szirtes. This has now joined Volume 1, ‘The Call of the Clerihew’ (2019) on my bookshelf (where a handful of mine previously found a home). The latest volume is available to purchase here: More Bloody Clerihews

Thanks, again to Andy Jackson, for publishing my offering entitled ‘Tolstoy’ for week 2 of his Double Dactyl website Double Dactyl of the Week on 24 October. I love this form, and will be writing more.

Many, many thanks to Gill Connors and Rebecca Jane Bilkau of Dragon Yaffle for including my poem ‘Elementary Inventory’ in the anthology ‘Up the Duff’ published in November. I am very grateful for the inclusion of this poem which is a particularly important one for me personally. Thank you both for all your hard work on the publication of this book, and congratulations to all the other contributing poets.

As a photographer, I find that many of my poems originate from a visual stimulus, so I’m always very happy to have a visual prompt every month from Visual Verse … and happier still when one of my poems is selected for the website, along with those of many poetry friends, including Angi Holden and Finola Scott to name just two. Thanks to Visual Verse for providing these stimulating challenges every month and thanks to the editors for including the following poems of mine on the website during 2022:

‘You will go down to the sea again’ January 2022 You-will-go-down-to-the-sea-again/

‘Down the Tubes’ June 2022 down-the-tubes/

‘First Class Mail’ November 2022 first-class-mail

Another of my poems ‘An Egyptologist’s Funeral Plan’ is scheduled for publication in the forthcoming ‘Gods and Monsters’ edition of ‘Here Comes Everyone Gods and Monsters issue’

Translation

I am always delighted when I manage to merge my love of Wales and Cymraeg with my love of poetry. An opportunity came as a result of being contacted in 2021 by Nicky and Elin of Ennyn, a community-centred, arts-based company based in Ceredigion, delivering bilingual educational workshops in schools and other communities. They commissioned singer Owen Shiers to sing the poem ‘Y Border Bach’ by William Williams (Crwys) and I had previously translated the same poem which Ennyn tracked down to my website: another-crwys-poem-translated. In 2022 my translation appeared on the Ennyn website for their Dolau Dyfi project, alongside a beautiful recording of Owen Shiers singing the song yn Gymraeg, and lovely photos of the singer! https://www.ennyncymru.com/owenshiersdolaudyfi

Of all the things I do in poetry, this has to be high on the list of things I’m most proud of being involved with, not least because Ennyn is based in Ceredigion, very much the land of my forefathers.

Reading at Events

Thanks to Veronica Aaronson for not only including a couple of my poems in the ‘Despite Knowing’ anthology in 2021, but for including me in the readers for the associated event at Teignmouth Poetry’s Mini Festival in May 2022. I have huge appreciation for Veronica’s vision for the anthology, and her hard work in curating and editing the poems and seeing the project through to publication. It was good to meet Veronica at the event and also to connect with other readers and participating poets at the festival, including Rosie Jackson and Hélène Demetriades (an opportunity for me to buy signed copies of their books!) It was also good to catch up with other poet friends, particularly Simon Williams, Tom Sastray, Rachael Clyne and Hannah Linden. I was honoured to read the poem ‘One Day Clean, and Counting’ by Hannah Stone during the festival, and my own poem ‘At the Apple Orchard Clinic for Eating Disorders’. Much appreciation to all the poets and organizers of this lovely festival. Poetry Teignmouth Festival 2022

Thanks to Sarah L Dixon for her hard work on the Quiet Compere tour, 2022. Her planning began early and was thorough and well-detailed; I learnt as early as February that I would be included later in the year, on one of the virtual sessions … and this came to fruition in August when I took part in one of the Zoom editions of the Quiet Compere. quiet-compere-stop-6-zoom

Much appreciation to Sarah for her multi-venue, in-real-life and virtual tour, throughout a demanding year, including a new full-time job … and being a fantastic Mum to Frank.

Collaborations: Running Workshops, Editing and Publishing

My long-standing association with Cheltenham Poetry Society sprung to life again, after a two-year pandemic hiatus, with the Awayday in May – day-long writing retreat at Dumbleton Hall. This was the eighth CPS Awayday, which had been annual event pre-pandemic. As always, I enjoyed working with CPS Chairman, Roger Turner, on the design and content of the day’s workshops on the theme of ‘The Elements’. The material included projected images, sound recordings and the text of poems by a variety of poets including Simon Armitage, Sylvia Plath, Philip Gross, Nigel McLoughlin, Rebecca Gethin and Holly Bars. We are delighted to have received 100% satisfied feedback from the attending poets after the Awayday, confirming that the workshops had helped with their writing and that they would like to do something similar in 2023. We must thank staff at Dumbleton Hall for another memorable Awayday, particularly Emily, the events coordinator. Dumbleton Hall

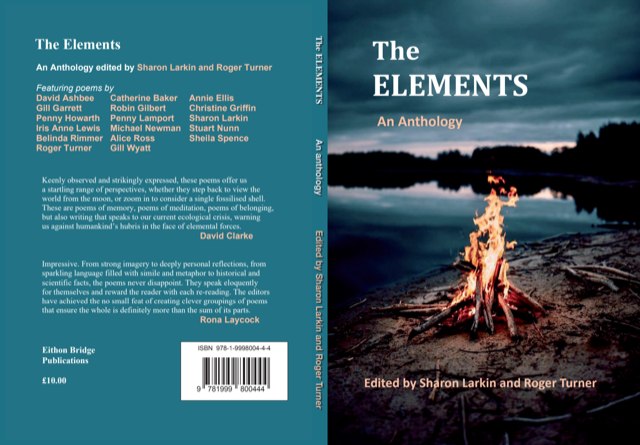

Over the summer, Roger and I co-selected and edited poems submitted by the Awayday poets, for inclusion in an anthology of poems and photographs on themes of earth, air, fire and water. ‘The Elements’ was published in November, as a joint Cheltenham Poetry Society and Gloucestershire Stanza venture, by my outfit, Eithon Bridge Publications. Thanks go to all of the poets attending the Awayday and submitting excellent poems for the anthology: Robin Gilbert, Iris Anne Lewis, Penny Howarth, Christine Griffin, Belinda Rimmer, Gill Garrett, Annie Ellis, Sheila Spence, Penny Lamport, Catherine Baker, Gill Wyatt, Alice Ross, David Ashbee, Michael Newman, Stuart Nunn, and of course Roger. Particular thanks go also to Kevin Woodward of Wheatley Printers Wheatley Printers in Stroud, Gloucestershire, who patiently worked with Roger and me through the process of setting the text, positioning photographs, finalising the cover design, and then the printing and finishing of the book. We were delighted with the resulting volume of 59 poems by 17 poets, and over 30 photographs. Thanks are also due to David Clarke and Rona Laycock who were generous in their words of endorsement for the cover, and additional words to help us publicise the book which can be purchased through Eithon Bridge Publications: Eithon Bridge The Elements. Below are some photos of the poets with their copies.

Attending Workshops

It was also good to reconvene during the second half of the year for monthly meetings of the CPS Writing Group. Thanks to chairman Roger Turner’s securing of a new venue, and thanks to all the Writing Group members for their helpful critiques and fine poems: Roger Turner, Michael Newman, David Ashbee, Stuart Nunn, Robin Gilbert, Sheila Spence and Gill Wyatt.

Later in the year, I was pleased to join a new fortnightly face-to-face group, Cleeve Poetry Writing Club, led by Claire Thelwell. Many thanks to her for her enthusiasm and commitment, and also especial thanks to Will Williams of The Cleeve Bookshop for allowing us to meet in his wonderful bookshop after hours. It’s the perfect venue, and a lovely group of poets. Thanks too to Jo Bell … again … since we are drawing on her book ‘52: Write a Poem a Week. Start Now. Keep Going’ (Nine Arches, 2015). I think this is the fourth time I have been drawn back to 52, after its ground-breaking initial run by Jo back in 2014. It is a timeless source of inspiration, available from the publisher: 52 at Nine Arches

In 2021 I began attending Mark Connors’ and Gill Lambert’s (now Connors!) Wednesday Wordship sessions on Zoom … and these continued through 2022. A previous blog post records my gratitude to them for all the good things that I have experienced personally from this dynamic poetry duo. Thanks to Yaffle

Assisting in a Competition

Not only did my ‘oeuvre’ grow by some twenty poems during the Wednesday WordshIp workshops, but I was honoured to be asked by Mark and Gill to offer my opinion on the short-listed poems in the 2022 Yaffle Competition, and to put them in order of the Top Ten, as I saw them. There was such a high standard that it was a challenge putting the ten poems in order of perceived merit. Having done so, I was delighted to learn subsequently that my recommendations aligned very closely with Mark’s and Gill’s own assessment – particularly in identifying the winning and commended poems. I was delighted that Mark and Gill used some of my comments on the poems in announcing the results. Yaffle Competition Results Congratulations to all the long-listed, short-listed, commended and highly commended poets and especially to winners Sue Burge (first), Ian Harker (second) and Holly Bars (third). And am pleased that one of my own Wednesday Wordship poems ‘You Knit’ will be included on an ‘honorary’ basis in the Whirlagust III prizewinners anthology. Thanks again to Mark and Gill Connors for an excellent poetry year.

Reviews, Written and Received

Another result of the collaboration with Mark and Gill was that I was asked by fellow Wordshipper, Holly Bars, to review, and write a cover endorsement for her debut collection ‘Dirty’ from Yaffle Press, launched in November and on sale here: Dirty It was a privilege to get to know Holly through Mark and Gill’s Wednesday Wordship sessions on Zoom in 2021/22, and an honour to be asked to write a response to her astonishing debut collection. Holly is definitely a poet to watch.

In August I was delighted to receive a 5 Star review on Amazon for my collection ‘Dualities’ (Hedgehog Press 2020): ‘Skilful poetry, a delightful collection of accomplished writing.’ Thanks to Ozymandias!

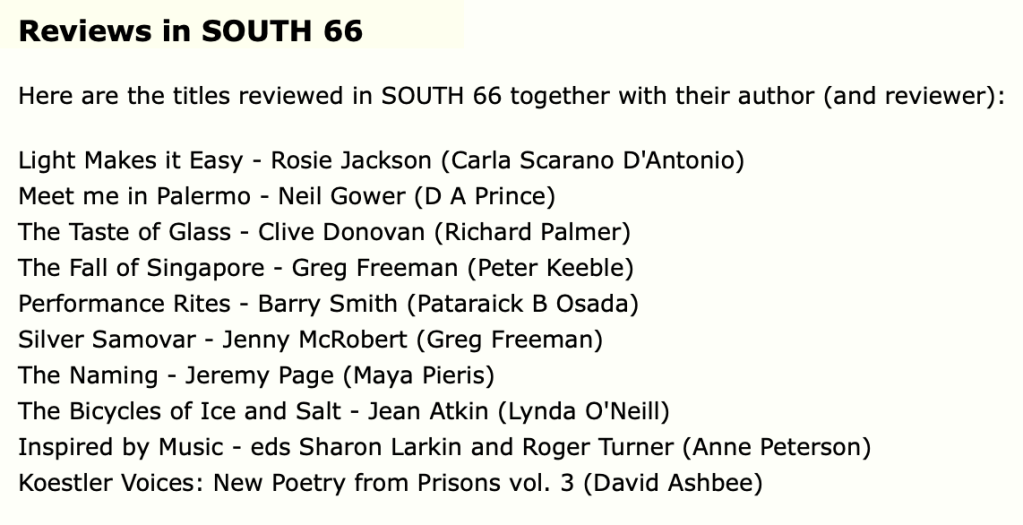

Finally, a big thank you to South Poetry Magazine South Magazine and especially Anne Peterson for the positive review of the ‘Inspired by Music’ anthology of poems and photographs edited by Roger Turner and me, and published on behalf of Cheltenham Poetry Society by Eithon Bridge Publications in November 2021. The review appeared in issue 66 of South Magazine in October 2022. The idea for an anthology inspired by music came from a desire for a project, for CPS poets, during the hiatus between the 2019 and 2022 Awayday writing retreats. The positive review for this anthology was most welcome! ‘Inspired by Music’ can be purchased through Eithon Bridge Publications: Eithon Bridge anthologies

Looking Forward

Overall, 2022 felt like a year of slowly getting back to something approaching ‘normal’ … whatever ‘normal’ is nowadays, but I hope 2023 will begin to feel like a leap forward, a change of gear, an acceleration towards goals still unfulfilled!

A happy, productive and successful 2023 to all poets, everywhere … and good health and prosperity to all people, wherever they happen to be.

The title of this review is a quotation from the poem Nightly, two thirds of the way through Zelda Chappel’s haunting and beautiful collection, The Girl in the Dog-tooth Coat, published by Bare Fiction Poetry (2015). Having read and reread the sixty poems in the collection, I can state categorically that I have failed to find a single line that disappoints.

The title of this review is a quotation from the poem Nightly, two thirds of the way through Zelda Chappel’s haunting and beautiful collection, The Girl in the Dog-tooth Coat, published by Bare Fiction Poetry (2015). Having read and reread the sixty poems in the collection, I can state categorically that I have failed to find a single line that disappoints.