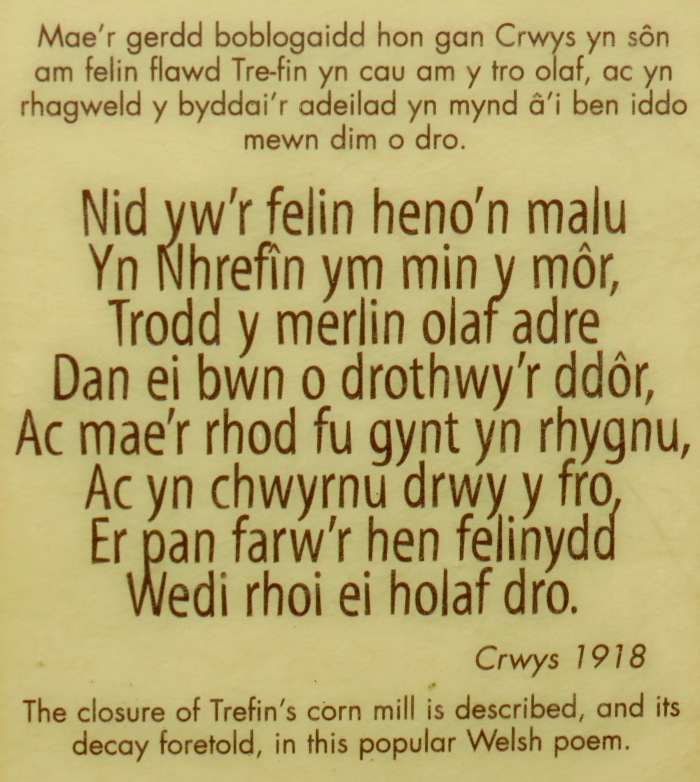

A few years ago, I was approached by fellow poet Chris Hemingway about a poem by William Williams Crwys that he had found on an information board at a ruined mill at Trefin in Pembrokeshire, I translated the poem here and several interesting spin-offs happened subsequently, including my trip to Trefin, visit to the mill and chapel, having my translation of Melin Trefin included in a tapestry at the chapel and a magazine, and being contacted by a descendant of Crwys, resident in the southern hemisphere, and consequently locating out-of-print books containing further poems by this well-loved Welsh poet.

It’s funny how these out-of-the-blue events develop a life of their own, and all seem to connect up in some mysterious way.

A few days ago, in early August 2020, I was contacted by someone whose father, soon to be celebrating his 90 birthday, has an interest in another poem by Crwys – Y Border Bach. I quickly located the text … and not so quickly … attempted a translation.

As with all translations of poetry, a literal rendition of the original language sacrifices the poetic language of the original. Rhymes, assonance, alliteration and …. in translating Welsh specifically, cynghanedd … are inevitably lost. However, if one strives towards preserving these elements in any translation, liberties have to be taken with the meaning, and the poet’s apparent intent. Compromise is therefore necessary.

I have made some decisions which stray a little from a literal translation in order to achieve a ‘feel’ for the original intent, as I perceive it. I believe Crwys wished the simplicity of the modest flower border in this poem to ‘stand for’ Wales, and Mam – the central figure, and ‘planter of the plant’ in any Welsh home – along with her neighbours, to represent the people of Wales. ‘Plant’ is the Welsh word for ‘children’.

With such a reading, it is possible to infer something about the showier blooms in the mansion gardens, and their ‘pedigrees’, as well as seeing the dandelion colonising the garden – as an upstart interloper.

As Crwys was a minister of religion as well as a poet – or rather a bard and an eisteddfodwr – other assumptions can be made. Particularly, the Old Man referred to in the poem, as well as being the common name for a specific garden plant, is more than likely a reference to God … especially as this ‘Sage’ is seen as standing over and caring for the other ‘plants’ in the border … ie the people of Cymru, and the speakers of the Iaith y Nefoedd (the ‘language of Heaven’).

As a lover of simple wild flowers rather than brightly coloured, highly bred garden flowers, I can relate to this poem. My Welsh father was of similar mind … “y pethau bychain” … the little things … were important to him, as was his garden, and always a preference for the unpretentious.

Here is the poem, followed by the translation. While I have learnt Welsh to an advanced level as an adult, I am, naturally and in all humility as a non-native speaker of Cymraeg, open to correction, So if Welsh is your mamiaith, please do comment in kindly manner if you detect error in my translation, or misinterpretation of the sense and intent of the poet. Thank you.

Y Border Bach

Gydag ymyl troetffordd gul

A rannai’r ardd yn ddwy,

‘Roedd gan fy mam ei border bach

O flodau perta’r plwy.

Gwreiddyn bach gan hwn a hon

Yn awr ac yn y man,

Fel yna’n ddigon syml y daeth

Yr Eden fach i’w rhan.

A, rywfodd, byddai lwc bob tro,

Ni wn i ddim paham,

Ond taerai ‘nhad na fethodd dim

A blannodd llaw fy mam.

Blodau syml pobol dlawd

Oeddynt, bron bob un,

A’r llysiau gwyrthiol berchid am

Eu lles yn fwy na’u llun.

Dacw nhw: y lili fach,

Mint a theim a mwsg,

Y safri fach a’r lafant pêr,

A llwyn o focs ynghwsg;

Dwy neu dair brlallen ffel,

A daffodil, bid siŵr,

A’r cyfan yn y border bach

Yng ngofal rhyw ‘hen ŵr’.

Dyna nhw’r gwerinaidd lu,

Heb un yn gwadu’i ach,

A gwelais wenyn gerddi’r plas

Ym mlodau’r border bach.

O bellter byd ‘rwy’n dod o hyd

I’w gweld dan haul a gwlith,

A briw i’m bron fu cael pwy ddydd

Heb gennad yn eu plith.

Hen estron gwyllt o ‘ddant y llew’,

A dirmyg lond ei wên.

Sut gwyddai’r hen doseddwr hy

Fod Mam yn mynd yn hen?

gan William Williams Crwys

Translation:

The Small Border

Along the edge of a narrow path

that divided the garden in two

my mother had her little border,

the prettiest flowers of the parish.

A little root of this and that,

here and there, now and again

and, in this way, a little Eden

came quite simply into being

somehow, by chance, every time.

I don’t know how, but Dad always

swore that nothing ever failed

when planted by the hand of Mam.

Yes, almost all the plants were

simple flowers of poor people

and miraculous vegetables, notable

for goodness rather than appearance.

Among them were snowdrops,

mint and thyme and moschatel,

winter savory, sweet lavender,

and a vigorous bush of box.

Two or three primroses

and daffodils were sure to be

– all the plants of the small border

in the care of some ‘old man’.

They were a host of common folk.

None of them in that small border

could claim the pedigrees of those

blooming in the mansion’s gardens.

With a stab to the chest one day,

I came across an old alien, wild,

without precedent in the border –

a dandelion blown in from a distance,

smiling an insolent smile

in sun and dew, and I wondered

how that old coloniser knew

that Mam was growing old.

Notes:

- Moschatel is Adoxa moschatellina, also known as muskroot or townhall clock.

- Old man is a common name for Artemisia abrotanum, also known as sagewood.

………….

Translated from the Welsh by Sharon Larkin, 3-5 August 2020